Robin Heath delivering this talk at the Temporary Temples Crop Circle Conference in the summer of 2018

Robin Heath is an independent researcher into ancient wisdom, specialising in archaeoastronomy and megalithic culture. He has written nine books on this and allied subjects, including the best selling Sun Moon & Stonehenge: Proof of High Culture in Ancient Britain, Power Points: Secret Rulers & Hidden Forces in the Landscape and Alexander Thom: Cracking the Stone Age Code. In a varied career Robin has enjoyed being a research scientist in computer chips, a marketing manager in electronics, a senior lecturer in mathematics and engineering and head of department in a college of further education. Since 1974 he has also been practicing as an astrologer and is a highly regarded astrologer who has taught in all the leading schools of astrology in the UK and been the editor of the international Astrological Association Journal.

You can find out more about Robin Heath and his work on his website: www.robinheath.info

If you are wondering how the word ‘megalith’ becomes relevant on a crop circle website, then prepare for a big surprise, as researcher Robin Heath compares the ‘language’ of stone circles with that of crop circles, and finds many more similarities than one might expect. This article also explores the reasons why both subjects remain excluded from within the establishment.

Learning the Megalithic Language

by Robin Heath

All text & Images © Robin Heath

Part One : Asking the Right Questions

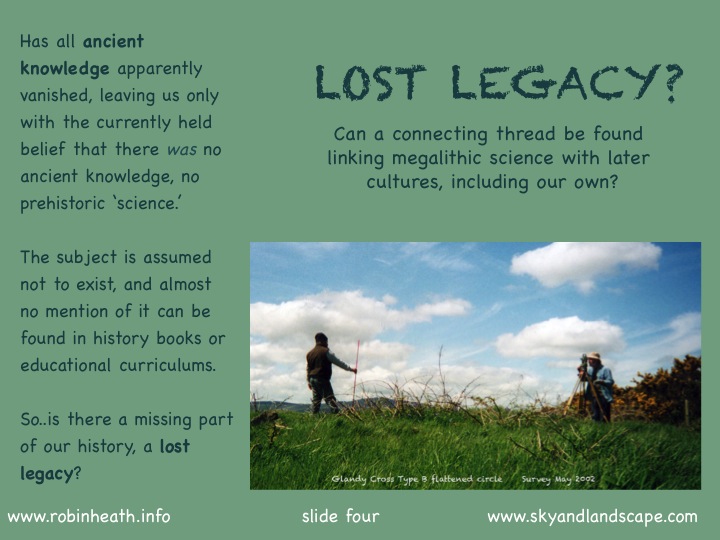

Fig 1. What from the megalith era has survived in to the present? Click on any of the images in this blog to see an enlarged version

Our connection with the megalithic culture has been sundered many times by the frequent and often massively disruptive cultural changes that inevitably followed the many serious incursions into all regions of this over-conquered land (Fig.1). Despite this, the British landscape still contains more surviving stone circles than can be found anywhere else in the world alongside many other remnants of what was once a thriving Neolithic culture. The ‘Boys’, as Alexander Thom called the megalithic builders, long before the arrival of political correctness, liked to erect megaliths – large stone monuments that remain filled with significant and recoverable cultural patterns from that period. Many thousands of these prehistoric monuments have survived intact and in an adequate enough condition to reveal their underlying design. These designs and their cultural patterns have not yet been embraced by prehistorians and archaeologists, and this type of evidence remains considered as bunk.

Fig. 2 The Megaliths were clearly once very important to the megalithic cultures, … why then are they no longer important now? What happened to the science underpinning these enigmatic monuments?

The evidence revealed over the past sixty years shows that the assessment of human knowledge and capabilities during prehistory has been massively underestimated (fig.2) and it has almost always appeared from outside of mainstream archaeology. The reasons for this are discussed later, and show that it is crucial that the present unsatisfactory situation be radically changed if we are ever to get inside the head of a designer of megaliths, the ‘astronomer ‘priest’ as was once the term.

Asking the Right Questions

Fortunately, the important questions that need to be asked, over and over again, are fairly obvious and they are easily asked. Anyone with an interest in ancient knowledge, aka the history or development of human culture or science, should be asking these questions each and every time they study a megalithic monument or structure (Fig. 3). We need to pick up our lost legacy.

The vital questions to be answered are:

Who designed these monuments? ; Who built them? ; Why are they there? & What were they for?

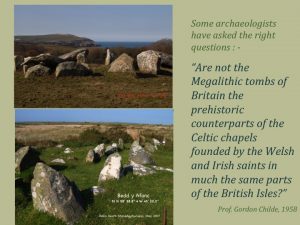

Some archaeologists have asked some right questions (Fig. 4). Despite this, the present ‘official’ or ‘establishment’ model of prehistory has not satisfactorily been able to answer any of the above questions. It will be argued here, that the archaeology profession has not even been looking in the right direction in order to find any answers, and secondly, the reason for this has been that training in archaeology starts from the arts side of the curriculum and does not include what are known as the number sciences.

I think it was the archaeologist and stone circle specialist Dr Aubrey Burl who noted that most of the breakthroughs in twentienth century prehistoric archaeology had come not from archaeologists, but from engineers and scientists. This was perhaps best epitomised by the introduction of one of the leading British scientists and a renowned cosmologist of the post-war period, professor Fred Hoyle, who wrote in the introduction to his book On Stonehenge [Freeman, 1977),

‘The remarkable story discussed and developed in this book goes I believe beyond anything the casual visitor might guess, for it requires that the men of the new stone age, men living 5000 years ago, to have been meticulous observers of the night sky, to have calculated with numbers, and to have communicated sophisticated astronomical knowledge among themselves from generation to generation. Since this assessment of the intellectual capacity of neolithic man much exceeds that which archaeologists and prehistorians have hitherto accorded to him, I have felt it important to review the case with care. …‘

Where archaeology has adopted scientific help, it has often struck gold in enlarging our understanding of prehistory. For example, the introduction of radiocarbon dating during the 1960s and 70s enabled prehistorians for the first time to closely determine when the construction of many megalithic monuments and their associated artifacts had taken place, often to within a couple of centuries or so.

The techniques involved in radiocarbon dating were heavily dependent on numerical and statistical analyses, and a giant leap in understanding the chronologies of the past was made by incorporating these techniques. One outcome was that many prehistoric monuments in Europe were shown to have been built prior to the Great Pyramid (c2650 BC), and that some major monuments in Europe were constructed before 5,000 BC.

The required adjustment to the existing prehistoric model created a time-warp within archaeology, with many casualties, but at least the question of when they were built had been satisfactorily answered, if not always to the delight of some archaeologists of that period! The then extant Theory of Diffusion, which had become a prime anchor explaining how civilisation(s) had originally spread from the eastern Mediterranean to western Europe during prehistory now lay in tatters.

Embracing a scientific i.e. a numerically based approach to the question: Why the Megaliths?, never seemed to be acceptable to the archaeologists of the 1960s and 1970s, although it spawned several unconnected outbursts of research which led to a general debunking of the whole business. Meanwhile, outside of the academy, ex-muris – a mountain of new evidence that provided many reasonable answers to our original questions was being revealed by scientists and engineers. We should take a peek at the contribution of three of the major players from this period, each very different from the others.

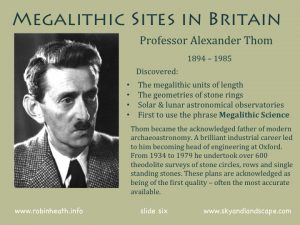

Alexander Thom

Professor Alexander Thom was a senior Oxford academic with a long and distinguished career as an industrial engineer, and his empirical findings shook the pillars of the archaeological establishment (Fig. 5). Thom is today acknowledged as the father of modern archaeastronomy, the first person to suggest through a huge weight of evidence that an entire cultural component of prehistory had been totally missed or ignored by academic prehistorians. This missing component was capable of answering our original questions, and greatly broadening our understanding of the megalith builders. When asked about what were the estimated capabilities of the megalith builders on a mainstream television documentary in 1970 Thom said, he immediately replied that:

“In terms of their thinking abilities I think they were, as far as brain power is concerned, my superiors.”

Euan MacKie

Thom’s findings galvanised an up and coming senior prehistorian, Dr Euan MacKie, to write Science and Society in Prehistoric Britain (Fig. 6). This book contained a collection of inconvenient evidence about prehistoric life that archaeology had conveniently chosen to play down or even hide from the wider public.

John Michell

John Michell (Fig. 7) was another of the prime movers and shakers of this subject. In the late sixties he kick-started the rising New Age movement into developing an interest in the legacy of lost knowledge – our legacy, which he saw as having been swept aside by the industrial revolution. Michell later became a pioneer in arousing interest into the new phenomenon of crop circles, and was the first person to attempt to integrate the science underpinning both megaliths and crop circles subjects, becoming the editor of the first magazine on the subject – the Cerealologist.

John was perhaps the first to notice something which the croppie community could today usefully pay more attention to, asking : – why are the crop circles so often located adjacent to Britain’s oldest sacred site – the builders of temporary temples like to put them near to the most permanent temples in the land?

Many crop circles use an adjacent prehistoric structure within their geometrical design, either as a datum point or anchor for the entire design. In other words, prehistoric sites often form an integral part of the crop circle’s geometry. Early researchers, such as geometer John Martineau, delighted the nascent crop circle movement with the discovery of pentagonal relationships between prehistoric sites and early Celtic ‘fours’ and ‘fives’, also some of the early pentagonal designs of the 80s. I ask the reader: Who today is working with this type of material, this evidence?

What are the Ancient Sciences?

The ancient sciences alluded to by each of these three revolutionary researchers drew from the ‘natural philosophy’ first written down by ancient Greeks. Throughout more recent historical periods, great men of science and philosophy have been drawn, through their observations of the natural world, to comment on the apparent order found in the Cosmos, the Grand Scheme of things, the apparent design. Prominent amongst these are Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, Pythagoras, the Islamic philosophers and more recently, Kepler, Newton and, Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642), who wrote (Italics mine),

‘Philosophy is written in this grand book – I mean the universe – which stands continually open to our gaze, but it cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the characters in which it is written. It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures, without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it; without these, one is wandering about in a dark labyrinth’.

Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642)

We have now arrived at an important stage in understanding how to answer our questions, for it must be clear to anyone who has spent time fathoming out the nature of either stone circles or crop circles they each are similarly ‘written in the language of mathematics, and (their) characters are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures .‘ Galileo’s remark tells us that both phenomena belong to the same category as do all cosmic truths, all created forms.

By Galileo’s own definition, both stone and crop circles carry universal truths. This must imply, if nothing else, that the people who conceived, designed and then built these forms on the landscape must have carried some knowledge of the language of mathematics and geometry. This being the case, why has so little interest or energy put into revealing that the mathematical and geometrical meanings from within the established institutions, whose job it is to answer our original questions (listed at the beginning of this article), one might have assumed? It was Thom who identified the components of the ancient sciences, these being Astronomy, Geometry and Metrology (the science of measurement), and who named it ‘megalithic science’. And it is this science that can answer our original questions.

One might also recognise that, despite our modern science and technology, many folk still appear to be wandering about in Galileo’s dark labyrinth, including some renowned archaeologists and scientists. They know nothing of ancient science, and often deny that it even existed.

Part Two : Crop Circles and Stone Circles

Fig. 8 The crop circle at Crooked Soley 2002 contained many numbers connected to ancient measure and astronomy.

If they have been able to plough through these first few paragraphs, observant croppies will probably have recognized that the above posited questions concerning prehistoric monuments are the very same questions that are most commonly asked concerning crop circles. This is our first connection. Furthermore, the official line on crop circles has similarly failed to answer any of the above questions. Curious, that, isn’t it? This is connection number two.

These first two connections, between stone and crop circles, tells the reader that researchers into either megalithic science and crop circles are asking identical questions. Both groups search out answers within similar official environments of denial, rebuttal, derision and ignoring of the evidence. Although seemingly very different in nature, both subjects find themselves banged up within much the same type of cage, where official recognition is always denied. To answer our original questions, this needs to change, even if that change comes from outside of the archaeological fraternity.

The Myth of Hoaxed versus Genuine

There is an altogether different kind of question commonly asked by croppies, and it also tends to be the first question that is asked by a querulous public. It is a question that makes study of this phenomenon rather different from that of megalithic monuments. It is this: –

Is crop circle X a genuine or a hoaxed specimen?

The truth is that there are much more salient questions to occupy the minds of croppies than determining how many per cent of crop circles are ‘fake’ and how many are ‘genuine’. One needs to first ask: Is anyone quite sure quite what these labels mean? If some covert group of people have been responsible for the production of all the designs of crop circles in all the many countries where they have appeared, or have franchised out the secret of their design and, perhaps more importantly, their implementation, and if they have done all that, and still managed to keep their identities totally secret, like Banksy nearly has, then we do indeed have a minor miracle on our hands. And the word fake becomes wholly inappropriate. If, however, they have not done all of these things, then a true mystery faces us, one that commands urgent attention. Crop circles then fit into the category of sacred art, uncontaminated by any formal identification with human involvement.

Until one has first attempted an answer to the earlier questions of how they were made, by whom and why, whether or not they are ‘genuine’ is a rather futile question to be dominating research into the phenomenon. Why? Because, regretfully, by lingering in this swamp of confusion and paranoia many otherwise good working friendships have been irrevocably sundered in outbreaks of ego, largely meaningless nit-picking and top-trumping games to achieve, well almost nothing!

This, sadly, is the present status of the crop circle subject, one where the croppie community can regularly be seen pressing the self-destruct button – destroying in this sad process any credibility in the subject. For every time we row amongst ourselves in public (and more recently, on the internet) we play straight into the hands of an establishment all too ready to sustain the false belief that crop circles can easily be explained away as a joke/all man-made/irrelevant/end of/nothing is going bump in the night/Ha-Ha, told you so/Lunatic Fringe!

Just because we do not yet fully understand the purpose of a 300 feet (100m) geometric design that ‘just appears’ overnight in a field of maturing cereal, it sure does not mean that its main purpose was that of expressing fakeness or genuineness and that it has no purpose beyond these two extremes. Faffing about with this polemic issue has not and probably can never solve the nature of a phenomenon that just goes on producing exquisite form in fields or maturing crops. Until we have footage of a man-made, i.e. ‘fake’, being made, that shows evidence of how the precision was attained and leaves a crop undamaged or spoiled by access, accidents or left litter, the jury’s out on ‘fakeness is proven at this or that circle’. We could really use a Haynes manual on the subject of crop circles and, more crucially, on who makes them and why?

The One Question that can be Answered

Fortunately, with work and experience one question can be answered, and Galileo would no doubt have been delighted! It is this:

What is the geometrical design?

Identifying or understanding the geometrical design of either a megalithic monument or a crop circle can be undertaken, but only when one has a plan, good aerial photograph or survey data. An understanding of that geometry is the important next step. Anyone capable of that task will soon find themselves in a most curious space, like Alice falling down the rabbit hole, for be these megalithic temples or temporary temples, they often contain very sophisticated geometries and inter-related numerical surprises. Some connect to others across the landscape like ancient stations placed on long disused railway lines (Fig. 9).

Some of the more complex designs employ the same numbers as Plato recommended in his commentary on the design of temples, as did other Greek and later philosophers in their descriptions of how a temple should be configured.

There is no need to be coy about any of this. Plato may not have had access to our modern knowledge yet there exists plenty of evidence to suggest that someone before him did. For example, the key dimensions of the earth (in miles and very accurate), based on his quoted ‘Temple’ numbers, are to be found built into the designs of several crop circles or stone circles. That alone begs a pretty enormous new question, eh?

If one detemines this statement to be true, and readers will have to ascertain that for themselves, crop circles become no longer a joke, nor irrelevant, nor likely made by nocturnal farmers with planks and ropes, who one might reasonably presume were not familiar with the works of Plato. It is at this point that crop circles and stone circles alike begin to reveal their awesome language to those who can comprehend it. A meaning emerges as to the purpose of these temporary temples and those of their Stone-Age ancestors. It has something to do with connecting their designs to the fundamental dimensions of the planet we inhabit. These designs are sometimes commensurate, and even use familiar units of measure like the foot and the cubit in their design. As yet, few can or do comprehend the significance of these things, for the essential dimensions have not traditionally been accurately recorded and this will also have to change if we are to answer our original questions.

The Establishment Model of the Megalithic Period

The current model of prehistory appears to be intentionally designed to present megalithic people as less capable than us, and more barbaric (could this be possible?). Our cultural model must keep up the mantra that we are superior to our ancestors. And although some megalithic monuments are sometimes referred to as temples by archaeologists, they often gain this title through a need for dramatic effect on often tedious TV documentaries rather than anyone having checked to see whether the monument under the lens conforms to later Platonic ideas on what a temple design should be.

The present cosy model of the megalithic culture we enjoy today has been built up over the past few centuries. It has always presented modern civilisation in a good light and the times in which we live as the most ‘civilised’ times yet. Linear social progress ad infinitum and let’s spread the milk of amnesia over the fact that almost all nature’s processes, including human ones, are cyclical and recurrent in nature. History bears ample witness to this inconvenient truth in its small print – The value of your civilisation may go down instead of up, and sometimes catastrophically quickly, violently and almost permanently. Like Hiroshima was, and as we are currently being asked to believe, like a hard Brexit would be.

The megalithic model held up for public display is therefore the complete opposite of what I believe megalithic culture aspired to. This also must change.

The Root of all Primitivism

The vision of Stone Age primitivity was first sown by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan, a political philosophy first published in 1651. The book was very much influenced by the on-going British civil war of Hobbes’s time, where his description of ancient mankind, the ‘state of nature‘ where humans without government ‘they warre of every man against every man‘ led directly to our ancestors living a life that was ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short‘. Curiously, most of this baleful description fits the historical record of the British civil war.

Hobbes’s basic assessment of ancient capabilities has lingered on into our times, and has influenced the top echelons of historical and archaeological research. Even the popular post-war prehistorian and media darling, professor Richard Atkinson referred to the ‘Howling Barbarians‘ (that built Stonehenge) as late as the early 60s. If one is led to ponder how Stonehenge or Avebury ever came to be built by Howling Barbarians, as serious study of either monument reveals that they clearly weren’t. They were built, as is obvious with only a tiny amount of thought, by engineers, stone-movers, astronomers, logistic experts and precision measurers and surveyors.

One consequence of the Hobbesian approach to ancient and prehistoric cultures is that, although one might reasonably think that the best way to understand the capabilities of the megalithic culture would be to go to a university and study the matter, in fact a) you couldn’t even if you wanted to, and b.) this would anyway be about the worst starting point for anyone who wanted to understand megalithic science.

The chips are stacked against you at square one, ever against encouraging anyone to search for evidence of a sophisticated system of weights and measures, counting skills, knowledge of the size of the earth, the commensurate surveying abilities and an operational understanding of the motions of the heavenly bodies, a working cosmology. Yet all this is there, in plain sight, like the treasure in Aladdin’s cave, waiting for the taking. It sits where it was originally located, on the sacred landscapes of Britain, Brittany, Ireland, Denmark and notable other places in Europe. You, yes you, could find it. It could be you that fathoms out more of what this astonishing culture was up to. I would recommend you do attempt to find out more, if only because prehistory properly assessed would show ancient humans up in a much better light, and our modern culture as being something of a bizarre aberration.

The Art of Wilful Intent in Academic Establishments

‘There is no reliable evidence for this!‘ is the standard flag held high whenever any researcher presents evidence that attempts to overturn the entrenched belief that our Neolithic ancestors were incapable of the skills-list presented in the preceding paragraph. Here’s a good and typical example. In the popular book Astronomy before the Telescope, a compilation produced for reading by the common man or woman, edited under the sharp monocled eye of the establishment astronomer Sir Patrick Moore.

In this book, concerning the megalith builders, Professor Clive Ruggles confidently tells his presumed non-specialist readers that:

‘There is no evidence of the use of astronomical observations for practical purposes such as determination of the time of year…

…the idea that distant horizon features could be used to pinpoint the motions of the sun or moon to a few minutes of arc have now been discounted.’

Doesn’t this plant a ‘factoid’ in the thought of a non-specialist reader? Dies it not suggest that there is no point even thinking of looking out for such things as a megalithic calendar, alignments to equinoxes and sunrises, alignments to major standstill rises and sets of the moon. Does it not suggest: “You’re wasting your time, we know better!”

Coming directly from the only Chair of Archaeoastronomy ever to be established in Britain, and now long gone, this quotation signals up two red warnings to the sharp investigative mind. The first warning sign was that Prof Ruggles may be thought to have failed to notice that the axis of the most visited and best known megalithic monument in the world, Stonehenge, has its axis and long avenue aligned to the point on the horizon where the midsummer sun would have risen at the time when this monument was built. Here is literally ‘time of year‘ manifest in stone, and it was first noted in our era by William Stukely, in 1741. Here we have a famous and universally known ‘distant horizon feature‘ being ‘used to pinpoint the motions of the (rising) sun at the midsummer solstice, and all this to a few minutes of a degree (arc).

If Ruggles sincerely believed what he wrote above to be the case, then we might be forgiven for thinking him underqualified for the job he was employed to do. It surely cannot be a good thing for the only professor of archaeoastronomy, an endangered species in Britain, to be telling everyone that the subject of precision megalithic astronomy never really existed, and is therefore not worth investigating, can it? If that’s the case then let’s just close the department down, then? Well, sadly, that is what ultimately happened.

If Ruggles had ever been bothered to measure the length of the Stonehenge Avenue in those units of length that were discovered and extensively researched by Professor Thom, he would have had a shock. From the centre of Stonehenge to the point where it terminates, where the avenue makes a sudden right angled bend towards the river Avon, he would have found that the length was 365 and a quarter megalithic fathoms. That’s the length of the year, the solar tropical year as professional astronomers would say. What is this length if it is not a ‘determination of the time of year’? This is not only a length of time, it is a daily diary measured along the axis of Stonehenge where one megalithic fathom along the avenue represents a single day within the year?

Ruggles certainly knew all about the megalithic fathom (5.44 feet) because he was fully familiar with the work of Professor Alexander Thom, and along with most archaeologists he refuted most aspects of his work, part of which contained details of a ‘family’ of megalithic unit of lengths employed to high levels of accuracy within megalithic structures all over Britain, Ireland and Brittany. A table of these was published a long while ago in[space]Megalithic Remains in Britain and Brittany (Oxford, 1978, p49). One can be certain that Ruggles would have read the evidence that supported this table of megalithic measures.

This leads me to a second red warning – there appears to be an hidden agenda operating in all this, one designed explicitly to switch people on to the idea that investigating the astronomical properties of megalithic monuments is a waste of time. Further support for the existence of this agenda was provided by the guide that was issued to his students about the degree courses he had planned and was to oversee at the only Archaeoastronomy degree course in the UK, that he chaired at Leicester. It is about his old adversary, professor Alexander Thom, acknowledged world-wide as being the pioneering modern Father of Archaeoastronomy.

In the brochure to students he stated,

‘Thom’s “megalithic astronomy“. In the course we do not consider the work of Alexander Thom and its re-assessment in any detail, partly because the subject is a very technical one and partly because many of the issues are no longer of archaeological interest.”

Megalithic monuments are not the only things that are reduced by this kind of treatment, but this bizarre comment makes the agenda blatently visible. It also confirms what Thom had to regularly deal with from his many opponents within mainstream archaeology.

The Establishment Model of the Crop Circle Phenomenon

The identical issues and treatments to be found within the subject of stone circles can also be found in the study of Crop Circles, wonderful temporary temples that began to appear in the late 70s, as if by magic. In the fields of southern Britain, and then in many areas around the globe these designs, like many megaliths, could be shown to carry a hugely sophisticated geometrical message within their design. As Dr Nick Kollerstrom once remarked, on air, “These designs are wholly new, none of them can be found in school geometry books.”

The model of megalithic society covered previously therefore cannot be applied to cover crop circles, because here the capabilities of their designers clearly lies beyond those of our present technology, and their understanding of geometry is sublimely beyond anything that may be found in those school geometry textbooks. Strange isn’t it that although both Doug and Dave are now both dead, exquisite crop circles, loads of them, continue to appear in fields throughout the land, and beyond, and yet nobody claims to have created them? That inconvenient little truth never sees the light of day in the press, does it?

It has been said in high places that crop circles could represent a threat to National Security. But this is clearly nothing like the threat presented by those Russian ‘tourists’ who recently claimed they had visited Salisbury simply in order to see the ‘interesting’ 123 metre spire of the Cathedral and the world’s oldest working clock. Oh, and this determined duo said that they may have wanted to visit Stonehenge, but there was ‘too much slush on the roads’. A far cry from Russia, then?

Megalithomaniacs and Croppies alike should rejoice that these two dangerous clowns did not make it to ‘boring’ Stonehenge, or ‘tiresome’ Old Sarum (Fig. 10), or, worse still, conflate their dastardly and unrealistic tourist trip with “we also came to see a crop circle, comrade” during their painful and shoddy interviews. The Novochok attack represented a real threat to National Security, not like the linear ‘ley’ between Stonehenge, Salisbury cathedral and Clearbury ring nor the precision geometrical patterns created by flattening wheat stems in a field.

Those that have studied crop circles, a fairly modern phenomenon, have similarly discovered that our academic institutions and our various press and media corporations provide no encouraging platform by which a seeker looking for what lies behind this phenomenon could ever enlarge their learning. Just as for megalithic monuments, this goal is best achieved, not by attempting to find a university course on the subject (there aren’t any), but in the case of crop circles by merely being on site in the fields around Wiltshire, Hampshire, Oxfordshire, Dorset and Warwickshire during the summer months. Much can be gleaned directly from the cornfields of southern Britain. “Hang out there, young man” (or woman) might be the best advice for those seeking some truth in understanding this latter day phenomenon, a truly modern mystery which to many people is also the best landscape art around.

What did you expect, then?

Neither Megalithomaniac nor Croppie need become embittered nor paranoid about the present state of public acceptance of their passion, for this is nothing new. Human institutions have often if not always behaved this way. Most virulently active in human religious systems, this treatment when facing new or perceived difficult subjects also ripples down through all our other social, political and educational systems. And even though these behaviour patterns of the human psyche, when faced with new ideas, have been explained perfectly well by modern psychology, the fact that so few institutions accept the psychological sciences as relevant merely demonstrates proof of this fact!

So what did you expect? Researchers in any new subject have habitually been presented to the public as eccentric, mistaken, deviant, misguided, evil, plain wrong or just mad. And while it is true that while they are entering that liminal space between the known and the unknown, many researchers do indeed take on or possess some or all of these qualities, because it is in the very nature of research that false starts, mistakes, weird coincidences and failed or incorrect axioms will be met with, have to be faced and routinely dealt with. It is in the very nature of research that nothing is yet established, the researcher is trying to establish something but has not yet arrived at the destination, and, of course, may never do.

Meanwhile, the Establishment, by definition, deals only with established ideas, while less attractive words can be seen tagging on behind, like entrenched, ossified, derelict and inflexible. Each of these can similarly be used to describe the massive resistance to change that is applied to major social, political, religious and industrial systems.

It is normal for any radical ‘newness’ to take a generation or two before these same institutions, and the people who populate them, suddenly begin to accept change, and start describing that previously ‘crazy theory by that weirdo guy’ in more glowing terms. Those same institutions and media giants that previously derided, ignored and ridiculed the ‘weirdo guys’, that ‘lunatic fringe’ lot, begin using wholly different adjectives, like ‘enlightened’, ‘pioneering’, even ‘brilliant’. Medals and other honours are struck, then conferred and pinned onto their champions, and big dinners are organised in honour of the inventor or researcher who has been thought to have finally ‘come good’. A cynic might even discover a correlation between this type of award and the ‘commercial viability’ of the end product of all that research.

University faculties and even buildings eventually become named after these people, even statues have been known to appear, usually long after the pioneering researcher or role model has passed away, and Wikipaedia then informs the world what a great guy this was, this bloke who once invented the better mousetrap, or Dynamite, or worked out the human genome, or found out how to keep more chickens in an even smaller cage. But Wikipaedia is also renowned for its constant inclusion of the less well known and weird predilections of those who have stepped outside what is considered ‘normal’. Completely irrelevant aspects like womanising, drunkenness, being gay, taking drugs or having an interest in astrology are often included in the package, rather like throwing so much dirty washing into a Hall of Fame, in order to somehow warn people not to try and emulate these great researchers of the unknown. (Try Newton’s entry, or John Michell, Kepler, Fred Hoyle, or Alan Turing if you want to see how this practice pans out).

So a good maxim to adopt might be to become less cynical about how things actually are, or rabbiting on about one’s hurt feelings because croppies and megalithic researchers have a raw deal in the press and are largely unrecognized by the larger culture. Remember this: just as is the physical reality for molecules of matter, it similarly takes both energy and time to re-shape the molecules of human thought towards new ideas. So, go wear your croppie T shirt or bluestone pendant with pride.

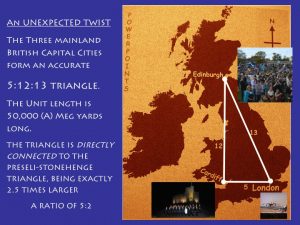

The study of megalithic monuments is markedly different from the crop circle phenomenon for it is not a new subject, despite the megaliths having their origins fixed in distant prehistoric times, only ever since Elizabethan times (comparatively modern-ish) have they increasingly aroused the interest of many people. The quest to determine their purpose has been taken up over a good five centuries and more by a plethora of well-shod and often well-meaning antiquarians, archaeologists, engineers, scientists and anthropologists. Researchers in the matter have each faced dead-ends, vicious criticism, failed theories, chronic inability to date the monuments, bad survey plans, and the universal failure of not being able to answer the most fundamental questions that every questioning soul asks when they encounter these leviathan monuments in the field for the first time : our original question from page one – What was it built for, why is it there“, and “what was its purpose“? We need to constantly remind ourselves that this question remains stubbornly unanswered by mainstream archaeologists. To answer it might mean that we can better come to understand why the centres of the three mainland capital cities of the UK, London, Edinburgh, Cardiff happen to define the corners of a second huge 5-12-13 triangle, again aligned to the Cardinal points and exactly 2.5 times larger than the Stonehenge – Lundy triangle to be discussed in more detail later (Fig. 11). The sharp end of this triangle is sited in on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, a Royal mile is 8/7ths of a mile and thus metrologically related to the root megalithic yard of 19.008/7 feet.

Something must be Missing

Some properties of megalithic monuments can be thought of as certain, and one of those is that they were not built for any whimsical purpose. Their sheer size yells ‘intent’ at even a casual observer or passing tourist. These monuments reveal themselves to have been built for a purpose, a reason, often at a particular premeditated and highly significant location, and if that purpose or that reason or that location cannot be fathomed out with the information and data that we already possess, within the present archaeological model of prehistory, then it is entirely logical to make the conclusion that prehistorian archaeologist Dr Euan Mackie made. In a film made by Glasgow University in 1970, he said of the profession’s failure to comprehend the work of professor Thom that:

‘something must therefore be missing from the education and training of archaeologists‘.

This simple sentence presents the researcher with perhaps the best explanation why modern archaeologists remain blind and disinterested in the study of megalithic monuments. The established order, those salaried professionals charged with understanding the megalithism of ancient times, well, in truth they aren’t well enough trained, at least in the numerical sciences. And like the old Sam Cooke pop song they “Don’t know much about geometry…” either, so they don’t understand, cannot understand, some even won’t understand very much about the mind set of the people who thought up, designed and then constructed thousands of what are, in effect, geometrical monuments all across Stone Age Europe.

If one would be ill-advised to sign up to do a university course in prehistoric monuments, (there isn’t such a course anyway), then just what is the alternative? Well, if it isn’t all about acquiring qualifications with the purpose of taking up a career in this branch of archaeology, which could reasonably be described as driving into a career cul de sac, as long as geometrical, astronomical and metrological properties of monuments are almost totally ignored, then one could do worse than start with the monuments themselves, and fortunately there are many hundreds of adequately preserved megalithic structures in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, Brittany, France, Denmark and a score more countries.

Obtain an accurate plan, for many monuments are well surveyed and recorded. Measure them carefully yourself if you can, with a tape. If you want to avoid some terrible mistakes with astronomy later on, you might usefully check that the survey plan accurately shows true north, and not magnetic grid north, which are not the same and vary considerably, depending on the location’s geology and the capricious nature of the earth’s magnetic field over time. In the field you will need to become your own expert, which will take time. Take your time and learn to read the language wisely. A study of surveying and navigation would greatly assist understanding of the mind of a megalith designer. A small but welcome sign of your growing competence would be when somebody identifies you as being a member of the lunatic fringe.

Measure the distance apart between monuments across the landscape, using Google Earth. It can reveal that networks of monuments are geometrically and metrologically connected together in large landscape arrays spread over many miles (Figs. 12-14 ). All very exciting – Indiana Jones stuff! During this process you will no doubt learn a lot about how little you know about defining and handling this kind of data. You will learn about accuracy of measurement. You will come to know that there are almost no straight lines possible when connecting two locations on a nearly spheroidal planet. To understand this even better, you might try wallpapering a large balloon as a practical task. Nobody has ever said this pathway would be easy, and sometimes it is more IKEA flat-pack than a walk in the park.

If this all sounds like hard times are ahead, then I respond by informing you that if you sincerely wish to leave the present stagnant paradigm behind, and cross over to a place where it becomes possible to gain knowledge concerning why those monuments are there, at that location, with the shape they have and doing what they do with other local monuments, then you will have to pay the ferryman the going fare. That is what this article is preparing the reader for: that work is involved in learning to speak the megalithic language.

We might usefully begin this process by exploring the available landscape upon which the various subjects that comprise megalithic science are located.

Galileo’s Universal Language

We will now look at the triangles, circles and other geometrical figures that Galileo identified in the earlier quote as being components of the language he is identifying. Without these components, mathematics and geometry, we cannot understand ‘a single word’ of the universe. His words, not mine.

Triangles are formed when three straight lines are drawn such that each line crosses over both the others at three separate locations. While nature offers many examples of circles, dead straight lines are not so common, and even the sea horizon is slightly curved by the near spherical shape of the earth. A spider hanging on a gossamer thread (in zero wind) is straight, as also is the downward path of heavy rain, the brief line of a falling piece of space debris, a high waterfall or the naturally formed facets of many crystalline forms.

It is surprise to many people when they discover that prehistoric and ancient cultures had a penchant for creating straight lines across the landscape. Whether these are, as Alfred Watkins first named them, ancient ‘leys’ or trackways, or something else, I leave to the reader to decide.

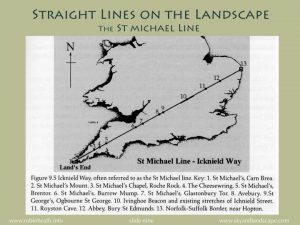

The eponymous Michael line is truly the longest line that can be drawn across southern Britain, embracing along its 365 mile path many high and holy places, appropriately dedicated to St Michael or St George (Fig. 9). However, the Michael line is not straight, for reasons well covered in the book, The Sun and the Serpent by the late Hamish Miller and Cornish author Paul Broadhurst.

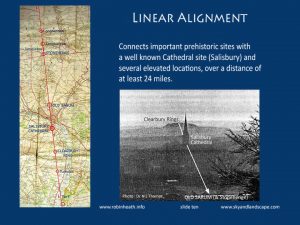

There is a little known and little publicised alignment that is truly straight, and it is very topical, for I am reliably informed by our media that even Russian spies are familiar with two of the sites along its length. Like the Michael line, it combines prehistoric sites with later church monuments. These monuments include Stonehenge and Salisbury Cathedral, Old Sarum and Clearbury ring, in addition to a row of four aligned tumuli, singleton tumuli and an unexpected number of long barrow sites including the Giants Grave, plus an ‘Iron Age’ fort. (Fig. 10)

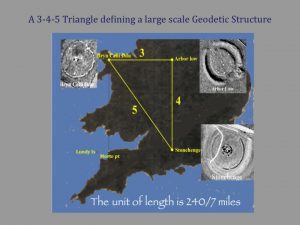

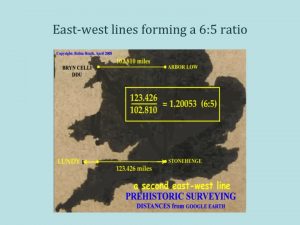

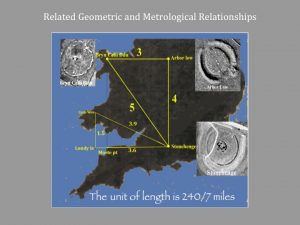

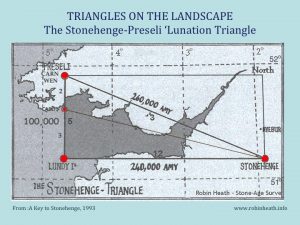

Taking the subject into far deeper waters, there is also a giant Pythagorean 5-12-13 triangle connecting Stonehenge with Lundy island, and the Bluestone region of the Preseli Hills, in West Wales. Beautifully aligned to the cardinal points of the compass, it uses the root megalithic yard, which is almost exactly 19/7 feet, in units of 20,000 to form a triangle whose dimensions are 100,000, 240,000 and 260,000 root megalithic yards (Fig. 15). Two of the monuments that define the triangles corners are natural features of the landscape, and very fixed, which translates into the interesting conclusion: ‘Stonehenge must have been the final location to be determined in this process, in order to complete this accurate, unlikely geometric message‘ In turn this then invites someone to answer the question: Why was so much effort expended into locating two so suitably sited locations in order to define the corners of an essentially invisible geodetic arrangement across south-western Britain? ‘.

The form isn’t 100% accurate, nor could it be, because I doubt if there is anyone today who could create such a shape across a similar landscape and seascape and get it any better defined. The sceptical reader should therefore trace it out on Google earth and note that the optimum form occurs only when the centre of Lundy is used for the right angle, and that this location is identical in latitude to the centre of Stonehenge at 51 degrees, 10 minutes and 43 seconds north. A line connecting these two points is truly east-west, by definition. So, how was this all done in Neolithic Britain – a big question, eh? While Google Earth is still on your computer or tablet, you might try connecting the centres of power in mainland Britain, by joining up the Capital cities of London (Westminster), Edinburgh (Holyrood) and Cardiff (Castle mound). The result should be compared with the Stonehenge-Lundy-Preseli blue stone site triangle, which is 2/5ths of the size, but uses the same unit of length, the root megalithic yard of 19.008/7 feet (see my book Power Points, 2007) for a full description.

As most crop circles are based on circles, triangles, polyhedrons, and thus similarly geometrical, and often (sad pun alert!) crop up adjacent to megalithic sites, we should not, by now, be startled when I suggest both phenomena are much more linked than we presently understand.

Conclusions

If the reader feels that the title of this article was misleading, apparently more like a maths lesson than a language class, then this exposes a deep inner prejudice. Even our dyed (died?) in the wool establishment culture redeems itself by upholding most strongly the belief that ‘mathematics is the universal language‘. How else could we ever expect to understand a megalithic culture that wrote nothing down, except through this universal language of mathematics, woven through the fabric and form of its many stone monuments as number, form and measure?

Megalithic monuments can be shown to have their nouns, adjectives, verbs, and even their idioms. However unlikely it would appear, their builders employed units of length that are still being used today. From such an unexpected fact we acquire some nouns that reveal a better understanding of how the megalithic language operates. It is possible to discover some astonishingly revealing sentences in that same language, that show clearly what was going on in the minds and hence within the culture of those who built the megaliths, and which, for reasons previously discussed, do not appear in the present model of prehistory.

A famous BBC documentary from 1970, based on this model, says of the stones that they appear to be “doing nothing, going nowhere“. Nothing could be further from the truth. Might this be a good description of our present culture? Surely, it has been our culture that has been ‘doing nothing, going nowhere‘ and thereby has therefore failed to notice, let alone understand, the kind of science incorporated into the many massive stone monuments – our surviving legacy from an astonishingly skilled and knowledgeable Neolithic culture.

A better understanding of astronomy, geometry and metrology, particularly of ratio and form, would enable students of megaliths and crop circles alike to change the future history of both subjects. Without grappling with the megalithic language described here we will never get close to our true legacy from prehistory, nor will we ever fully understand megalithic monuments or crop circles.

Robin Heath

2019

Coming Soon…

Part Two: Fuzziness & Precision

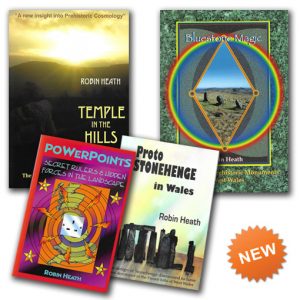

Buy books by Robin Heath

Buy books by Robin Heath

We have a selection of Robin’s excellent books on our online shop. Click here to browse and buy

A Selection of Books by Robin Heath an internationally published author on the subject of ancient science, he is well known and widely respected on the UK lecture circuit (including at the Temporary Temples conference) and has been awarded an Honorary Research Fellowship within the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Wales, Lampeter.

Recent Comments